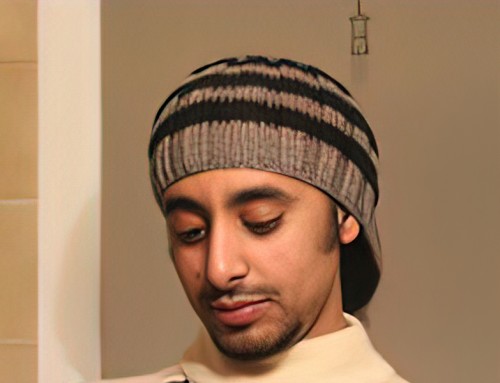

Kussay Moselmani, enlightened intercultural mediator

Lawyer, interpreter, translator, expert at the Bordeaux Court of Appeal and intercultural mediator, the Syrian Kussay Moselmani is all these things at the same time. He is above all a committed man who defends the role of intercultural mediation in the hosting of refugees.

Kussay Moselmani, a discreet and elegant man in his forties, has been living in France for almost twenty years. However, nothing predisposed this lawyer, a barrister and lecturer at the Damascus University to settle in France. Arabic and English speaker, it was by chance that he was given the opportunity to complete his training in France, as he did not speak a word of French. “I studied French for five months in Damascus before arriving in Bordeaux to begin my studies,” he explains in a perfect French.

Bordeaux, the source of light

Bordeaux is not the result of chance but of an informed choice. “During my studies in Syria, Montesquieu and “L’Esprit des lois” had made a strong impression on me. When I realised that Bordeaux was the city of Montesquieu, I said to myself that I had to go to the source of the light. I was fascinated by these men who founded principles such as the separation of powers.

A Master’s degree in Business and Corporate Law and another in International Law and Political Science later, Kussay began a PhD thesis on international trade.

However, he does not plan to stay in France and thinks of going back to Syria after his studies in order to work again as a lawyer. The war in his country changed his plans: “This radical change shook me, I had to react, I couldn’t go back to Syria. I wondered what I was going to do as a job here. I couldn’t see myself taking the lawyer’s exam in France, I didn’t even try”. It was in this context that Kussay found a vocation in intercultural mediation work. “Syrian compatriots were arriving in France. They were lost, overwhelmed, as were the social workers who took care of them. I wanted to bring something to both sides, to favour the integration of those who arrived and to contribute to the evolution of the practice of institutions concerning foreigners, to change their way of looking at things”.

Birth of a vocation

It is now 2011. Kussay started working, initially on a voluntary basis, in associations. He has the advantage of being fluent in Arabic, English and French and enjoys being the interface between the administration, the integration actors and the growing number of asylum seekers and refugees. “In a way, I felt I had a moral duty towards the society that had welcomed me. Not in the sense that I would have been indebted, but rather because I thought I could, at my level, change the situation. I began to understand what the role of an intercultural mediator could be: to help resolve conflicts, to mediate between the parties, to dispel misunderstandings, amalgams and stereotypes: “sometimes civil servants and social workers judge the “Other” on his or her instantaneous behaviour, but the reality is often more complex.

For Kussay, one of the important roles of the mediator is to try to change the way people look at things, to work on transformation: “he then becomes an actor, makes the most of his knowledge of the two cultures, tries to resolve the difficulties, and thinks of ways of doing things.

Laying the foundations for an equal encounter

The former Syrian lawyer readily quotes the text “Intercultural mediators, bridges of identities” by Margalit Cohen-Emerique and Sonia Fayman, but also Freud on the question of identity and culture, “that through which the subject conceptualises the world”, before continuing: “the Other does not have the same culture, the same view of life, the same philosophy. In this sense, they could be a threat, or at least a strangeness. The gap exists. My job is to prepare the ground for the encounter and the welcome.

Kussay claims to do this work in both directions. To the migrant, he explains the values and cultural codes of the society he arrives in; “I explain, for example, that here, looking in the eyes is not a sign of desire or disrespect”.

The same goes for civil servants and social workers: “I give them an insight into the behaviour of newcomers”. And he concludes “my role is to lay the foundations for an egalitarian encounter. To be able to create the conditions for an exchange of equals in order to avoid the relationship being doomed to failure.

“When I have a conviction, I go all the way”.

In more than ten years of intercultural mediation and interpreting, Kussay has seen the flow of Syrian refugees dry up. His compatriots are no longer arriving in large numbers, but his commitment has not gone down and he now works with families, teenagers, men and women from Iraq, Libya, Chad, Somalia and Sudan seeking asylum in France. Among his qualities, Kussay puts commitment at the top of his list: “when I have a conviction, I go all the way”. A commitment that he puts at the service of an intelligent, sensitive and peaceful mediation.

Verbatim

“Syrian compatriots arrived in France. They were lost, overwhelmed, as were the social actors who took care of them. I wanted to bring something to both sides, to encourage the integration of those who arrived and to contribute to change the practice of institutions concerning foreigners, to change the way they look at things. ”

“Sometimes officials and social workers judge the Other by his or her instantaneous behaviour, but this does not always reflect a reality.

“My role is to lay the foundations for an egalitarian encounter. To be able to create the conditions for an exchange of equals in order to avoid the relationship being doomed to failure.”